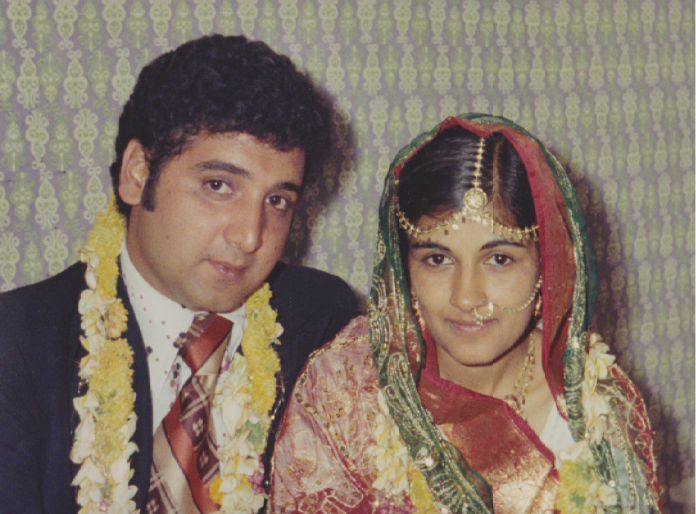

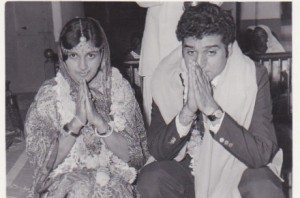

It’s always a pleasant rarity to see my mum and pops actually sit for a meal together at home. After 40 years of marriage in the UK, along with their individual work commitments, the traditional Indian ritual of “I will only eat with my husband” is neither applicable nor is it practical if one spouse comes home much later than the other. In doing so, my mother’s loyalty to my father is hardly questionable is it? Let’s be real ladies, when hunger strikes, a girl’s got to eat! Yet this week, millions of married women across the world, including the UK, followed the Indian ritual called Karva Chauth.

On this particular day, a married woman fasts between sunrise and moonrise as a means of wishing for her husband’s well-being and longevity. Interlacing the validation of a woman’s loyalty to her husband along with the celebration of the joys of sisterhood amongst other married women and those wishing to be married one day, it’s one of many Hindu traditions that is constantly under scrutiny for endorsing patriarchy.

I should have known in advance that my question on Facebook aimed at my Indian married friends as to who would be participating in this custom would prompt an array of emotions, most of which were fiercely defensive with multi tones of offence. Why do women follow such customs that can be perceived as portraying the male gender as superior and in turn devaluing our own being? When do men ever fast for a woman’s long life? Is gender inequality and misogyny difficult to eradicate if women continue to participate in such traditions?

The roots of Karva Chauth are derived from a mixture of mythological and historic origins. Karva meaning pot, and Chauth meaning the fourth day, as this ceremony falls on the fourth day of the Hindu month Kartik, is often associated with praying for a good harvest, and the traditional Karva pots were used to store wheat. History also narrates how women would save and prepare banquets of food as their husbands went to war to fight the Mogul invaders, hence rationing was interpreted as a fast for many believers. One of the most renowned traditional stories is that of Satyavan and Savatri. Scriptures describe how Savatri begged the Lord Yama to restore her deceased husband Satyavan back to life. It was only through her refusal to eat and her request for children with Satyavan as the father, did the Lora Yama acknowledge this Pati-Vrat (fasting for the husband) and granted back her husband’s life.

The roots of Karva Chauth are derived from a mixture of mythological and historic origins. Karva meaning pot, and Chauth meaning the fourth day, as this ceremony falls on the fourth day of the Hindu month Kartik, is often associated with praying for a good harvest, and the traditional Karva pots were used to store wheat. History also narrates how women would save and prepare banquets of food as their husbands went to war to fight the Mogul invaders, hence rationing was interpreted as a fast for many believers. One of the most renowned traditional stories is that of Satyavan and Savatri. Scriptures describe how Savatri begged the Lord Yama to restore her deceased husband Satyavan back to life. It was only through her refusal to eat and her request for children with Satyavan as the father, did the Lora Yama acknowledge this Pati-Vrat (fasting for the husband) and granted back her husband’s life.

This idolisation of the male species was a lot closer to home than I chose to acknowledge as a young teenager. At the age of 15, I recall how my friends and I were instructed that by undertaking the Jaya Parvati fast, whereby one simple meal a day is consumed for five days, God would bless me with my rich Prince Charming (P.S Dear God, I think mine got lost somewhere on the way!)

For my sisters and me, our consent to take part was solely the result of what any teenager would do – we followed the crowd. As a means to entice us, participants to stay up all night on the fifth and final night, known as Jaagran, we were awarded the “Jaagran special” – three Bollywood films in the local cinema all night. Result!

Fasts such as these that were carried out during my grandmother’s and even mother’s era, as one friend correctly pointed out, probably had an element of romanticism attached to it. Through this form of devotion, they were raised to believe that eventually a handsome hero would become a girl’s soulmate and saviour, hence completing her reason for being on this Earth. After all, it was the man that validated a woman’s status! Personally for me, at 15 the word marriage seemed like a lifetime punishment. After all boys of my age were, “weird” and I would think, why would I want to be stuck with one forever? (I’m still trying to figure out the answer to that one!)

Culturally male members of the family, right from the fathers and brothers to the husbands, are often placed on that invisible pedestal within the home and catered to ahead of any female. “Practically it probably stems back to how men have historically been the main income earners and women were at home with the ability to ‘silver service’ men,” says my aunt. Admittedly, I am still anticipating the reversal of roles where the men in the family will let the woman eat first as they prepare the chapattis! Wishful thinking some may say!

Let’s not forget that even the hip and trendy filmmaker Karan Johar’s Bollywood movies didn’t fail to remind us that “Pati parmeshwar hota hai” (the husband is equivalent to God). In the 2000’s, as Indian cinema started trending towards the depiction of female strength, I cringed during Johar’s Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham, as I watched the row of aunties nod in a unified silent agreement as Jaya Bachchan touches the feet of her deity in the form of her husband, Mr Amitabh Bachchan. “Yes, that’s why she’s so happy. Because she kept her husband happy!” screams the undertone of the scene.

Let’s come back to the reality of today, in the 21st century, where stereotypes have and continue to be challenged. Is Karva Chauth really just another patriarchal custom to ensure the females are reminded of their inferiority which conditions women to a submissive way of living? With women walking shoulder to shoulder with their male counterparts, earning equally and sometimes more than them, is this sacrificial expectation contradictory of what a woman has fought for over decades – her identity?

“ Women in our family have never been allowed to fast for Karva Chauth”, explains one young mother, “My great grandfather had set this rule of not fasting because women are considered Shakti, meaning strength, therefore Shakti cannot be treated as oppressed. It is our belief that the Goddess Parvati was also the epitome of Shakti (strength) who raised the off-spring and was worshipped as the pillar of a family. Without her, Lord Shiva was incomplete.”

Her views are echoed amongst many of my friends who all have daughters. One mother bluntly states, “I’m not even acknowledging this is as even a ‘thing’ to my daughter”, whilst another friend says, “Putting any human being on practically the same pedestal as God is beyond me. Moreover, if women are expected to do it then so should men.”

So why in 2016, for women who are perceived as empowered and independent, is Karva Chauth so important? Karva Chauth for many women across the world goes beyond the concept of “starving for your man” or placing a husband or fiancé at the same level of a deity. Another story around the origin of this custom stems from when young brides would form friendships with other surrounding married women as a means of breaking the sense of isolation within their newfound strange environment. These new friends were known as “kangan-sahelis” or “dharam-ben”, meaning god-like friends for life; and through this friendship they travelled the same walk of life. Karva Chauth was a celebration of this sisterhood, where they would buy each other new Karvas (pots) dress in beautiful attire and adorn themselves with jewels.

In India today, this form of attachment is just as widely acknowledged if not mandatory to the Karva Chauth celebrations. Fasting is just one element of the day for many of my friends and family in India, who treat this day as gratitude for sisterhood and friendship. Dressing up, applying henna and cooking delicacies is not for the sole purpose of pleasing the husband, but also for the simple joys in collectively doing so.

In India today, this form of attachment is just as widely acknowledged if not mandatory to the Karva Chauth celebrations. Fasting is just one element of the day for many of my friends and family in India, who treat this day as gratitude for sisterhood and friendship. Dressing up, applying henna and cooking delicacies is not for the sole purpose of pleasing the husband, but also for the simple joys in collectively doing so.

A similar sentiment is also felt amongst Indians here in the UK. The Asian Today’s editor Anita Chumber describes Karva Chauth as a symbol of her marriage and loyalty to her husband. She says, “It feels like it brings us together as we both attend the prayer at the Mandir (temple) and listen to the story of Deepali each year.”

Family and friends of mine in the UK chose to adhere to this custom from a personal element of an attachment to their upbringing. My married cousin sister who moved from Delhi to London three years ago says “I can’t explain why I do it, but I’ve watched my mum do it for years for my dad, and it’s the one thing that I choose to hold on to. It’s my choice.”

My mother, who has been independent from a very young age, still recalls her first Karva Chauth. Away from home, she was void of family surroundings in a foreign country and wanted to express her elation of experiencing being the young Indian bride. Even today, she strongly believes that this wasn’t a reflection on whether my father perceived her as an equal or not; this was her inner young woman wanting to be part of something she had only ever witnessed. The logical Indian that my father is of course, denied a custom that he described as “backwards and unnecessary.” My mum naturally was upset and didn’t continue on thereafter, but there was a little sense of relief in my mind that I was raised by a father who fiercely defended a woman’s right to equality.

Our culture is enriched with traditions and customs that are often subject to both elation and speculation, including that of Sati, where Sita jumped in the fire to prove her chastity to Lord Ram. Karva Chauth is just one of many rituals that interlink Indian women to something that is personal to them – good or bad. Ultimately, whether we choose to participate or even acknowledge it, the choice to uphold this belief is still a woman’s own choice.

Originally extracted from sejalsehmi.com