I’m not a parent. I cannot begin to comprehend the pain felt by the parents of Asad Khan at the loss of their 11 year old son. I cannot fathom what drove a young boy, with a bright future, to such despair that he felt that ending his own life was the only escape route from being bullied. What I do know is that no single person has the right to make any human being’s life feel worthless. So why does it happen? And as Asians, how transparent are we in our conversations surrounding bullying?

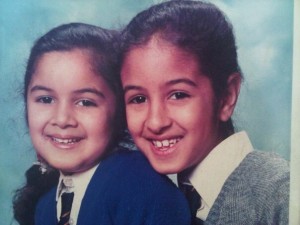

Last Sunday, I was invited to BBC Radio London to be part of Sunny and Shay’s panel along with Anisa Subedar and other guests to delve a little deeper into this extremely sensitive but growing issue. Admittedly, I wasn’t initially sure if my contribution would add much value as fortunately, my sisters and I were never traumatised to this extent of bullying. Sure, there were the usual run of the mill “she hates me and leaves me out” fights with our peers, but nothing that we couldn’t handle, or should I say, weren’t taught to resolve.

As I listened to the detrimental impact of the ‘girl on girl’ bullying some of the panel members had faced, I was thankful for all those times my mother would shamelessly call out on anyone who tried to make the other feel inferior. As an arrogant teenager, in my own words at the time, “I hated my life and wanted to die in shame” because of the sheer embarrassment of my mother’s method of resolving conflicts as one big “happy” family! But to some of my friends, who had to tackle bullying in the form of racism in the 80’s, and had limited conversations with their parents because of work constraints, my family’s techniques were a blessing in disguise and indirectly prepping me for the harsh reality of the adult world.

My mother was a victim of bullying in India. When she moved from Kenya to Gujarat, she was the object of speculation and her attire and well-spoken manner in the English language was enough to make her an easy target for her schoolmates. Being the teacher’s favourite and isolated to a separate corner of the room simply added fuel to those that probably envied her. At boarding school, talking to your parents about such trivial matters wasn’t an option; after all they were working every hour that God had sent to be able to provide my mum with the best education – an education that many were void of and a point that was etched permanently in her mind. Thankfully, my mother was surrounded by a group of strong friends who shielded her from the spiteful remarks and encouraged her to take pride in being a strong student.

My mother was a victim of bullying in India. When she moved from Kenya to Gujarat, she was the object of speculation and her attire and well-spoken manner in the English language was enough to make her an easy target for her schoolmates. Being the teacher’s favourite and isolated to a separate corner of the room simply added fuel to those that probably envied her. At boarding school, talking to your parents about such trivial matters wasn’t an option; after all they were working every hour that God had sent to be able to provide my mum with the best education – an education that many were void of and a point that was etched permanently in her mind. Thankfully, my mother was surrounded by a group of strong friends who shielded her from the spiteful remarks and encouraged her to take pride in being a strong student.

Growing up and being educated in the UK, my aunt dismissed racial “Paki” remarks as pure ignorance. “I would simply tell people to go and learn the difference between countries,” she says. Yet it was the inter-race bullying that proved more hurtful, as she and her sisters endured inconsiderate remarks on how they dressed or how they spoke.

In 2016, the decision to move out of the EU in the near future, i.e. Brexit, may have certainly ignited the ignorant excuses to display explicit racist abuse, especially in schools, but there is still a distinct alarm of lack of empowerment within Asians that’s drawn from a sense of insecurity. Many South Asians born in the UK are no strangers to being encouraged to go beyond their academic ability. Of course it’s a stereotype to assume that ALL Asian parents push the next generation to follow the typical medicine, law or accountancy fields along with the reminder of “I came to this country with nothing”, but statistics back up the work and education ethos (details available in the BBC radio clip below).

No matter which way we want to push the pendulum between our parents being too pushy and involved across to being too busy to notice and not pushy enough, those who are the exception still stand out and sadly sometimes pay the price for it. My cousin would often remark that during secondary school, no kid wanted to be seen as the extra smart one, “that’s just not cool!” And yet BBC’s Sunny struggled to fit in with the crowd at school because of his academic weakness.

My mum knew the boundaries with her parents and hence just embraced her struggles and dealt with it, there was no other choice. Choice in our generation has been highlighted as our right and we have infinite avenues to express our grievances. But today, where we are fortunate to be amongst such diversity within schools, parents on the panel felt the transparency of resolving a conflict is lost. Everything spoken has to deemed as politically correct, dare we offend anyone in what we say, how we say it and who we say it to. Some parents and relatives on the panel of children who had been bullied in school were denied open conversations with parents of the perpetrators.

However, what scares me personally is this new form of cowardice and persistence: trolling, otherwise known as cyber bullying. It’s the silent form of bullying that builds to a new level of cruelty at such a universal level because for our generation, that platform was non-existent until now. Today’s children are raised in a cohort where social media sets the form of social identity and recognition, where children as young as ten are craving for outside acceptance over self-respect. However much parents try and enforce internet restrictions within the homes, the ugly head of internet trolling still find its way out. And adults are sometimes equally to blame towards this contribution. Just this week it was reported in the Metro how a mother had reportedly shaved her child’s hair off as a punishment for laughing at a cancer patient, and then proceeded to post the video on social media. Is this the precedence parents set for the future generation?

The psyche of a bully who finds joy in making another individual feel inferior stems down to their upbringing and lack of mental well being. How unhappy must these bullies be in their own lives to torment another human being? Do Asians acknowledge or admit their own children as offenders? Victim vs bully – it’s these roles that both need to be diminished if we have the courage to acknowledge the reality of these silent cries and prevent the loss of another Asad.

Listen to the full BBC Radio London Sunny and Shay programme here.

If you are the victim of bullying or know anyone that needs help, please call Childline on 0800 1111.