Last week Hindus across the globe celebrated Jamnashtami, the birth of Lord Krishna, who was also known as Draupadi’s protector. In one of the most distinct moments in the epic Hindu mythological story, Mahabharat, it was Lord Krishna who prevented the public disrobing of Draupadi by the Kauravas. Her five husbands, the Pandavas, helplessly looked away in the name of family honour after losing all material wealth to the Kauravas in a gambling game, and had placed their wife’s dignity at stake. Incidentally, last week, the infamous “burkini” ban in France, (which has now been reportedly lifted), caused world-wide outrage as pictures emerged of women in these modest swimsuits, being publicly asked to remove these garments, by none other than police officers. The irony just screams at you.

Identifying one’s cultural background from their attire is not an alien concept in many cities across the world. Sikhs are often recognised by their turbans, Jewish men by their Kippah (caps), and South Asians by their saris and so forth.

The creator of the Burkini, Aheda Zanetti, had aimed to create an outfit so that her niece could participate in the netball court in an outfit deemed acceptable in her culture. “I created it to allow for freedom, not for it to be taken away,” she stated to the Guardian. Furthermore, it was also designed for any woman wishing to conceal their modesty due to some form of body self-consciousness; in short the aim was to create another choice.

Choice – a word I’ve probably always taken for granted; growing up as a British Indian in London, I was taught that having a choice was my right as a human being. This right grasped its true value during my school and university years where I witnessed girls of my age void from what some perceived as the luxury of choice. Oppression for some girls led to rebellion, as they fumbled in the school changing rooms from fully covered clothes to barely there skirts. Equally, there were women who wore headscarves out of choice and beamed with pride; proud that their choice of outfit did not reflect their capability to perform and integrate as well as their peers.

Choice – a word I’ve probably always taken for granted; growing up as a British Indian in London, I was taught that having a choice was my right as a human being. This right grasped its true value during my school and university years where I witnessed girls of my age void from what some perceived as the luxury of choice. Oppression for some girls led to rebellion, as they fumbled in the school changing rooms from fully covered clothes to barely there skirts. Equally, there were women who wore headscarves out of choice and beamed with pride; proud that their choice of outfit did not reflect their capability to perform and integrate as well as their peers.

It’s very easy to digitally shout on social media “oppression leads to segregation, ban all burqas!” but what’s to be said for women for whom the word “choice” is omitted from their vocabulary? My maternal grandmother was raised in a village where they had to conform to social rules such as limited or no education and arranged marriages. Dressing modestly (i.e. a sari) and covering their heads in front of a male or senior family member was the correct code of conduct for females in a typical Indian household.

In contrast, my mother was allowed to be educated in the city of Mumbai where in the 1960’s, the Western clothing market was booming, assisted by the trends of fancy beehive hairstyles and tight leggings fashioned by every other Indian actress. Any passenger who jumped on board this new train of chic would often be classed as brash and rebellious, my mum admits. It was of course a taste of Western indulgence, but in no way a reflection of her cultural beliefs, and in time the practicality and generation shift of attire became transparent to people like my grandparents.

Cultural views aside, I am the eldest of three daughters, and we were, correction STILL are, my daddy’s little princesses. It’s a dad thing- no man is ever good enough for his daughter and the dad is the daughter’s first hero because he was the first hand our little fingers grabbed onto. I still remember the day I first wore a halter-neck top in front of my father; it was unnerving! The anxiousness I felt had NOTHING to do with how I feel I should be dressing as part of my culture per se. But in the same way, when my father had first heard the word “boyfriend”, a similar sense of slight despair was felt that daddy’s girl was no longer that, a girl– she was a woman.

“But women have FAR more choice in attire than men both in casual and work environments,” debates a male friend who works in fashion retail. He continues with “if you walk into a woman’s clothes shop and then a men’s clothes shop you can instantly tell the difference in choice. If you are going to restrict yourself by only wearing certain clothes for your religion or job role, then you will remain limited.” As a male, he often feels he is judged on his fashion sense, which is deemed as pushing the boundaries of the norm. He states, “I once went on a blind date with an Indian girl who asked me if I was gay. The reason – I was dressed in red chinos and a tweed blazer! We are judged no matter whether we conform or not!”

Yet, what some may call choice, is often experienced by women as social responsibility. When questioned on this topic, a male relative states, “men’s clothing is polysemic: the same outfit can function in multiple contexts and translate into communicative meaning.” He continues on to say, “women do not have that luxury. They have to own many clothes because there are many contexts and many meanings, and their clothes are used as a weapon to judge them. Just go and talk to any cop who’s dealt with sexual abuse cases and one of the first things he’ll mention is what the woman was wearing, as if a dress was a justification for her attack.”

Is forcing more constraints on what a woman may wear or not wear making her daily life any easier? Or are women faced with more rules to abide by? Just this week, there were reports of India’s tourist minister issuing welcome kits to foreign nationals including a side note on appropriate attire. “For their own safety, women foreign tourists should not wear short dresses and skirts. Indian culture is different from the western.”

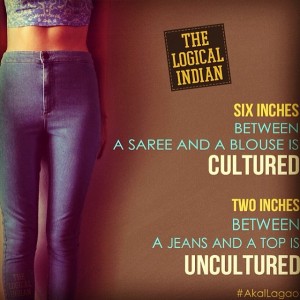

The interpretation of this message was speculated as “minimal clothing equates to asking to be attacked!” Is a midriff on display via a sari less enticing than a woman in a crop trop? As a foreigner in India, with the exception of cities like Mumbai and Delhi, no matter how hard I try and “blend-in,” I will always stick out like a sore thumb. I should clarify, however, that my choice to dress modestly when visiting certain places in India is not a formal shield to avoid being sexually attacked.

A few years ago, I volunteered as an English tutor in Mumbai for a charity who provided additional English classes for children from under-privileged backgrounds with minimal understanding of Western civilisation. These children are accustomed to living in one bedroom studio flats with at least three or four siblings and some are no strangers to witnessing open sexual activity between their parents. The request from the charity to avoid wearing shorts or clothing of a revealing nature was simply to ensure a child’s mind that was already of a disturbed nature, was focused on the subject they had come to learn. Social conduct and appreciation, inevitably begins at home, but the charity encouraged social behavioural classes and it was my choice to ensure my clothing (or lack of) wasn’t the distraction.

As I woman, yes I have felt that I do bear an amount of responsibility in my attire depending on my external environment. But I have the liberty in choosing as I see fit and above all what I am comfortable in. In an ideal world, as a woman I could walk out the door at any time and not be “asking for it”, or deemed as “uncultured” because of my skirt not reaching my knees. But the reality is that we are judged on every aspect of the choices that we make. A well-known journalist recently undertook an experiment where she sported the burka for a day to assess reactions of the outside world. Jeers, jibes and racist remarks overwhelmed her with fear, and it was just a hint of the kind of stereotypes that have been created.

It’s easy for women like us in a western world to stampede down the streets with our “fight oppression” banners, when there are women everyday in countries like Saudi Arabia who are fighting for their rights to simple things that we take for granted – driving, swimming or just showing their faces. Thousands of women’s screams still go unheard as they battle to hold onto their dignity in a bid to avoid becoming ISIS sex slaves.

So what gives another human being the right to remove a woman’s modesty and dignity? When the women in France were publicly ordered to strip, where was the CONSENT? Today it is the woman who wanted a little freedom in a public place in a modest outfit, who will it be next? If we stop tarnishing everyone with the same brush, maybe we can stop another Draupadi being disrobed.

Orginally published in sejalsehmi.com