British Museum exhibit offers visitors a chance to experience Muslim pilgrimage

By Shelina Zahra Janmohamed

QAISRA Khan and I are standing in the Round Reading Room of the world-renowned British Museum in London.

Around us people are busy installing historic artefacts from the Muslim world relating to the hajj, the pilgrimage to Mecca – a principal religious obligation of adult Muslims.

Khan is one of the curators of the exhibit “Hajj: Journey to the heart of Islam”, which opened on the 26th of January at the British Museum. She is visibly excited that those who are not Muslim will finally get to vicariously experience the pilgrimage through this pioneering exhibit. Relics painstakingly gathered from public and private collections from the UK, Saudi Arabia and other parts of the world are on display. Loans from Saudi Arabia include a seetanah, an embroidered cloth that parts in the middle to allow entry into the Kaaba itself when being used. The reds and blues which surround the stitched Arabic calligraphy highlight the richness of the Qur’anic text that adorns the cloth.

The exhibit offers the opportunity to hear about both contemporary and historic pilgrim experiences. My eye is caught by an original map identifying the possible routes for the Hijaz Railway, which was planned by the Ottoman official Haji Mukhtar Bey during his own hajj.

On the other side of the hall is a brightly coloured, almost cartoonish image of a group of people. Among them is a pilgrim, standing on the edge of a sandy plane surrounded by intense blue. It is a painting from southern Egypt, where for hundreds of years members of small villages have painted these images to depict the departure of the pilgrims.

When it comes to Muslims, Khan says, “All we hear about is ‘sharia’, and actually this is one of the few times when there is none of that – it’s just about what it is like to be Muslim.” Her aspiration is that visitors will be granted this experience.

It is a profound sentiment and one which calls for further reflection: What does it feel like to stand in someone else’s shoes and experience the world from their perspective?

The Hajj is a primary instance of creating connections with other people by sharing space and time with them. As pilgrimages go, it is not the largest in scale, but it certainly has the most diverse group of participants –bringing together people from over 180 nationalities last year.

Amongst the historic artefacts in the exhibit is a 15th century painting from Shiraz (in modern day Iran) which depicts a throng of people inside the haram, or holy sanctuary, in Mecca. The artist has depicted a sea of humanity with skin tones from black to white and every shade in between.

On the other side of the hall is a photograph from 2009 showing contemporary pilgrims at the desert of Arafat where pilgrims journey for forgiveness. Again, the faces are a portrait of humanity, joined together in their single quest for forgiveness, united by the same simple white clothing, all external differences erased. Any pilgrim who joins can’t help but get to know those from different countries and cultures and in turn be changed by the realisation of their shared humanity.

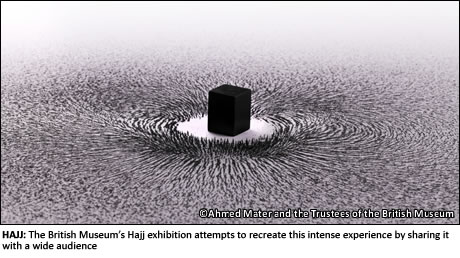

The British Museum’s Hajj exhibition attempts to recreate this intense experience by sharing it with a wide audience.

Such co-sharing of space and time is crucial to our development of empathy, and triggers an instinctive willingness to help others. The event of Hajj is an epic experience, but taking action to create empathy is something that happens on a day-to-day level too. We human beings can create this kind of empathy by supporting others in what they feel is important.

I have seen this in action at a mosque in London, which organised for its congregation to attend midnight mass at Christmas to create bonds with the local Christian community. And when I was living and working in Bahrain, I saw Sunni Muslims show their support and understanding when Shia Muslims commemorated Ashura, a ritual day of mourning, by sending food so that their Shia friends would not be detained by chores on a day of great importance to them.

Sharing experiences is vital to creating emotional bonds and support. Although this exhibition is a historic and cultural enterprise, and refreshingly apolitical, it offers visitors – Muslim or non-Muslim alike – the chance to stand in someone else’s shoes for a moment. And that is something, in our world of unfortunate divisions, which is always to be welcomed.

Shelina Zahra Janmohamed is the author of Love in a Headscarf and blogs at www.spirit21.co.uk. This article was written for the Common Ground News Service (CGNews).

Khan is one of the curators of the exhibit “Hajj: Journey to the heart of Islam”, which opened on the 26th of January at the British Museum. She is visibly excited that those who are not Muslim will finally get to vicariously experience the pilgrimage through this pioneering exhibit. Relics painstakingly gathered from public and private collections from the UK, Saudi Arabia and other parts of the world are on display. Loans from Saudi Arabia include a seetanah, an embroidered cloth that parts in the middle to allow entry into the Kaaba itself when being used. The reds and blues which surround the stitched Arabic calligraphy highlight the richness of the Qur’anic text that adorns the cloth.

The exhibit offers the opportunity to hear about both contemporary and historic pilgrim experiences. My eye is caught by an original map identifying the possible routes for the Hijaz Railway, which was planned by the Ottoman official Haji Mukhtar Bey during his own hajj.

On the other side of the hall is a brightly coloured, almost cartoonish image of a group of people. Among them is a pilgrim, standing on the edge of a sandy plane surrounded by intense blue. It is a painting from southern Egypt, where for hundreds of years members of small villages have painted these images to depict the departure of the pilgrims.

When it comes to Muslims, Khan says, “All we hear about is ‘sharia’, and actually this is one of the few times when there is none of that – it’s just about what it is like to be Muslim.” Her aspiration is that visitors will be granted this experience.

It is a profound sentiment and one which calls for further reflection: What does it feel like to stand in someone else’s shoes and experience the world from their perspective?

The Hajj is a primary instance of creating connections with other people by sharing space and time with them. As pilgrimages go, it is not the largest in scale, but it certainly has the most diverse group of participants –bringing together people from over 180 nationalities last year.

Amongst the historic artefacts in the exhibit is a 15th century painting from Shiraz (in modern day Iran) which depicts a throng of people inside the haram, or holy sanctuary, in Mecca. The artist has depicted a sea of humanity with skin tones from black to white and every shade in between.

On the other side of the hall is a photograph from 2009 showing contemporary pilgrims at the desert of Arafat where pilgrims journey for forgiveness. Again, the faces are a portrait of humanity, joined together in their single quest for forgiveness, united by the same simple white clothing, all external differences erased. Any pilgrim who joins can’t help but get to know those from different countries and cultures and in turn be changed by the realisation of their shared humanity.

The British Museum’s Hajj exhibition attempts to recreate this intense experience by sharing it with a wide audience.

Such co-sharing of space and time is crucial to our development of empathy, and triggers an instinctive willingness to help others. The event of Hajj is an epic experience, but taking action to create empathy is something that happens on a day-to-day level too. We human beings can create this kind of empathy by supporting others in what they feel is important.

I have seen this in action at a mosque in London, which organised for its congregation to attend midnight mass at Christmas to create bonds with the local Christian community. And when I was living and working in Bahrain, I saw Sunni Muslims show their support and understanding when Shia Muslims commemorated Ashura, a ritual day of mourning, by sending food so that their Shia friends would not be detained by chores on a day of great importance to them.

Sharing experiences is vital to creating emotional bonds and support. Although this exhibition is a historic and cultural enterprise, and refreshingly apolitical, it offers visitors – Muslim or non-Muslim alike – the chance to stand in someone else’s shoes for a moment. And that is something, in our world of unfortunate divisions, which is always to be welcomed.

Shelina Zahra Janmohamed is the author of Love in a Headscarf and blogs at www.spirit21.co.uk. This article was written for the Common Ground News Service (CGNews).