Britain to remember Noor Inayat Khan

By Zakia Yousaf

SHE was one of Britain’s most heroic citizens – a secret agent in the Second World War who worked at risk to herself day in day out as a radio operator in occupied Paris.

After being betrayed and captured by the Germans she remained heroic to her final days refusing to reveal the secrets that would lead to the deaths of many of those who she was entrusted to help. She was executed by an SS officer on September 13, 1944 at the Dachau concentration camp at the age of 30. Britain posthumously awarded her the George Cross for her extraordinary bravery, France honoured her with the Criox de Guerre, and today memorials in her name can be found in Paris and Dachau.

But who was this heroic woman and why has her story remained silent in Britain for so many years?

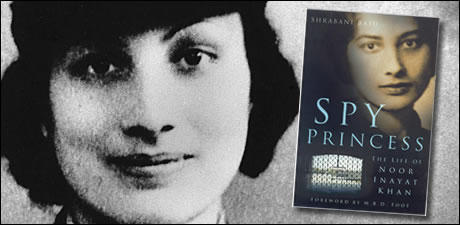

The woman in question was Noor Inayat Khan, a Muslim woman of Indian heritage and a British Spy who gave up her own life to help save Britain. Her story may have been lost in history but her legacy will shine bright after a campaign to have a memorial erected in central London in her memory was finally given the green light.

The founder of that campaign – The Noor Inayat Khan Memorial Trust is author Shrabani Basu who has fought hard for Britain to officially acknowledge the sacrifice made by Noor for this country.

Like many I had never heard of Noor until I read Shrabani’s 2006 book ‘Spy Princess: The Life of Noor Inayat Khan’. I was shocked, not only at my own failings for not knowing of her courageous story, but by how her memory has seemingly been buried at the bottom of British world war history – until now.

Shrabani’s book – which took over three years to complete – told the story of Noor’s childhood moving from Russia, where she was born, to England and then finally to France. A descendant of the legendary Tipu Sultan, the eighteenth-century Muslim ruler who died in the struggle against the British, Noor was a musician and writer before she began training as a nurse with the Red Cross on the outbreak of war. In May 1940 as Germany invaded France she escaped to England with her mother and siblings. And it was in London where she was to start a journey that would eventually lead her to a German concentration camp.

With her family settling in their new home in England, Noor joined the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force and trained as a wireless operator.

While working at a RAF bomber station, her ability to speak French fluently brought her to the attention of the Special Operations Executive (SOE) – an elite network of secret agents set up by Winston Churchill.

Noor agreed to become a British special agent – and despite misgivings by her superiors about her abilities as an undercover agent she was flown to Le Mans with the codename ‘Madeline’ and became the first woman to be infiltrated into enemy occupied France working for the ‘Prosper’ resistance network in Paris.

But soon after arriving disaster struck when many of her colleagues were arrested by the Gestapo – Nazi Germany’s official secret police network.

Fearing the group had been infiltrated by a German spy Noor was ordered to return home – but she refused saying that as the only wireless operator left in the group her position was vital.

She continued with her work keeping the SOE in London informed by wireless about developments. She attempted to rebuild the Prosper Network and heroically facilitated the escape of 30 airmen shot down in France.

But her bravery was to come to a dramatic end. Just months after beginning her life as a British secret agent Noor was captured by the Gestapo.

She was interrogated and although she remained silent they discovered a book in her possession where she had recorded the messages she had been sending and receiving. The Gestapo broke her code and were able to send false information to SOE in London.

In September 1944, after months of interrogation and torture, Noor and three other SOE agents were taken to the Dachau concentration camp where she was shot.

This is the story that author Shrabani wants acknowledged by Britain.

She came across Noor’s story in a newspaper article during research on the contribution of Indians to World War II.

She came across Noor’s story in a newspaper article during research on the contribution of Indians to World War II.

“It was just five lines about her and it intrigued me,” Shrabani tells The Asian Today.

“I wanted to know how an Indian woman became a secret agent in Europe. I wanted to know her background and I wanted to know the full story of her bravery. So I began researching her life.”

Basu says she was quickly drawn into Noor’s story and her “extraordinary bravery.”

“It was amazing how a gentle person like Noor – a writer and a musician – could take on the Gestapo in one of the most dangerous areas of the war in occupied Paris,” she says. “And it was inspiring to see how she remained defiant till the end and did not give out any names despite torture and interrogation.”

Despite her bravery Noor’s story was somehow lost in history – a fact that astonished Shrabani.

“I was amazed that I had never heard of Noor either in India or Britain. I soon realised that while she was highly decorated after the war she had been completely forgotten over the years.”

When Shrabani’s 2006 book ‘Spy Princess’ was published readers became fascinated by Noor’s story and inundated the author with letters asking why Britain had not officially recognised her sacrifice with a memorial.

“One reader suggested the fourth plinth on Trafalgar Square, another offered to write letters to the Prime Minister,” Shrabani reveals.

“School teachers wrote to me saying they were planning assemblies on Noor. In Manchester, a group of Year Six students brought out an illustrated booklet on Noor imagining the letters she may have written from her prison in Germany. Of course, Noor never had access to pen or paper in prison and could not write any letters but it was a poignant tribute to her from 11-year-olds.”

Shrabani said she realised how Noor’s story had “touched ordinary people, especially the young.”

“I felt it was all the more important to remember Noor’s message, her ideals and her courage in the troubled times we live in,” she added.

“Noor was one of only three women from the SOE to be awarded the George Cross, but while her colleagues from the SOE have blue plaques, memorials and museums in their honour, she has been forgotten.

“In Paris there is a plaque outside her family home in Suresnes. A band plays outside her house every year on Bastille Day to remember her help for the French Resistance. A leafy square in Suresnes has been named Cours Madeleine after her (Noor’s code-name was Madeline).

“There is a plaque in her honour in Dachau Concentration camp and another in Grignon where she made her first transmission. London had to catch up.”

With The Noor Inayat Khan Memorial Trust in operation Shrabani wanted the memorial to be in Gordon Square, near the house on Taviton Street where Noor spent her days as a young girl.

But the campaign faced huge challenges none more so than the fact that the land was now owned by the University of London.

When Shrabani applied for a blue plaque it was rejected on technical grounds, but things took a better turn when Labour M.P Valerie Vaz heard of the campaign.

Determined to help with the cause Valerie tabled an Early Day

Motion in Parliament and got the support of 34 MPs, while Shrabani accumulated signatures from a number of eminent Asian women including Human Rights campaigner Shami Chakrabarti and British Film director Gurinder Chadha.

With support for the memorial now in full-flow the campaign went back to the University of London for permission – which was finally granted.

Shrabani describes that moment as “wonderful” adding she broke the news to Noor’s delighted brother Hidayat, 94, sister Claire and nephews.

Now Patron of the Memorial Trust, Valerie praises the efforts of those will have helped make Noor’s memorial a reality.

“Everyone involved in the project is so enthusiastic and passionate,” she told The Asian Today. “They are a propelling force which has had a great impact.”

And the memorial may just be the beginning in preserving the memory of Britain’s Muslim spy princess.

“This project is meaningful for many people,” says Valerie. “For example, there is interest from a school in my constituency of Walsall South, who want to learn about her achievements and her tragic death. It is important that we recognise the contribution of women and people of diverse backgrounds to the history of our country, and I think the story of Noor will make a valuable addition to the curriculum.”

The Memorial campaign are now looking to raise £70,000 needed to create a bust of Noor and accompanying pedestal. Fundraising ideas are being brainstormed, donations are trickling in and even Bollywood is getting involved – film director Kiran Rao allowed her latest film ‘Dhobi Ghat’ to be part of a fundraising event for the memorial last month. “Her inspiring story deserves recognition,” Kiran said of Noor, adding the screening was dedicated to Noor “and her extraordinary courage.”

The Noor Inayat Khan Memorial Trust is confident the money will be raised in time for a grand unveiling in 2012.

Understandably Shrabani is excited about the prospect of seeing Noor’s memorial in Gordon Square. “This is the first Memorial to an Asian woman in Britain,” she says. “It will also be the first memorial to a Muslim in Britain. This is about our heritage and celebrating the life of a brave heroine.”

For more information on The Noor Inayat Khan Memorial Trust and how to make a donation log onto