How a human rights group is determined to end police brutality in Pakistan

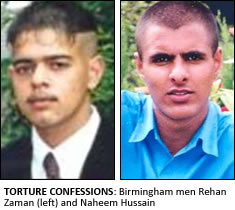

SIX years ago two Birmingham friends were arrested in Pakistan on suspicion of murder. Naheem Hussain and Rehan Zaman were charged with a crime they say they didn’t commit, but today they remain in a Mirpur jail, held without charge and facing the death penalty.

SIX years ago two Birmingham friends were arrested in Pakistan on suspicion of murder. Naheem Hussain and Rehan Zaman were charged with a crime they say they didn’t commit, but today they remain in a Mirpur jail, held without charge and facing the death penalty.

The case against them is based on confessions from the pair – beaten out of them until they had no choice but to admit guilt in a bid to stop the excruciating torture that was inflicted on them.

Naheem’s father, Fazal Hussain, was also arrested and thrown into jail along with his son. Freed and now back in Birmingham, he described the abuse his son suffered at the hands of the Pakistan police in a press conference last year.

“They beat us by kicking, sticks and any other way. They would never stop beating me and my son. For hours my son was on the floor, with two policemen – one holding his legs, one holding his arms – and a third one standing on his stomach, kicking.”

Reprieve, a human rights group, say torture practices are common in Pakistan prisons – but they have made it clear it has to stop.

Police abuse appears to be so common in Pakistan that it has been accepted as the norm, even though Pakistan has formally pledged to end these practices by signing the UN Convention Against Torture.

The Pakistan Police Torture Project was launched by Reprieve in July in a bid to tackle what they call ‘medieval practices’.

The project is inspired by the groups work defending British citizens on Pakistan’s death row, which they say reveals consistent evidence of widespread police torture across the region.

The group said standard abuses in Pakistani prisons included falaka, a form of foot whipping with a rod or cane, fingernails being pulled out, hot chillies rubbed into the eyes, being hung from the ceiling until the shoulders dislocate and severe beatings.

Since the summer Reprieve has been working up and down the country to gather witness statements from British Pakistani’s who have been on the unfortunate end of Pakistan’s ruthless police culture.

In a Birmingham office a team of volunteers are still hard at work trudging their way through a countless stream of witness statements.

One volunteer, Nawaz Hanif, has witnessed himself the horrific nature of the Pakistan prison system.

He was arrested in Pakistan along with his father for murder – a crime they say they did not commit.

“I saw things I will never forget for the rest of my adult life,” Nawaz tells The Asian Today.

“I can definitely say that the police took no notice of guilt or innocence, age or gender. One of the worst torture victims I saw was actually in my cell. One of his arms arm was limp and pale with the lack of blood because it was chained to the very top of a cell door for extreme lengths of time and whenever the guards opened the door, they dragged his lifeless body out with him.”

Nawaz’s father is now back in Birmingham having spent four years in Mirpur Central Jail

For obvious reasons Nawaz tells us the project “means a lot” to him and his father.

“We genuinely believe we can play a role ending torture in Police stations across Pakistan and Azad Kashmir,” Nawaz says. “The only way to do so is to take the illegal and inhumane practice out of the dark back rooms of police stations, and expose it to the world.”

Since the summer Nawaz has spent time reaching out to the British Pakistan community, urging victims of torture to come forward.

The group has leafleted in Birmingham, Bradford, London, Leeds and Cardiff, displayed posters in the heart of the British Pakistani community, and spoken to thousands of worshippers in Mosques.

They also used Pakistan’s recent cricketing tour of England to publicise the project, sending a team to Leeds during a One Day International between the two sides.

In Birmingham the family of Naheem Hussain have also thrown their support behind the project, helping to leaflet in the Alum Rock area of the city.

Nawaz reveals both Naheem and Rehan are aware of Reprieve’s project and are “extremely enthusiastic” about the scheme and the potential changes it can bring about.

Witness statements taken by the group reveals some shocking experiences.

One man, Nawaz tells us, was tortured simply because he was a British citizen.

“He was tortured for no discernible reason, other than his nationality. He was tortured for being a British citizen and not paying bribes to the police, and this was made clear to him whilst he was being made to suffer degrading and excruciating forms of torture. Whilst he is a British national, he was born in Pakistan and still has relatives there.”

But while Nawaz describes the response to the Project as “amazing”, he admits they still need more torture sufferers to come forward.

“Despite fantastic support from the people we speak to, we haven’t had the number of victims we expected to have when we initially embarked on the Project,” Nawaz admits.

“We have spoken to and contacted upwards of 10,000 people through Masjid talks, announcements and posters displayed in cities as far and wide as London, Leeds and Cardiff.

“But the amount of victims that we have spoken to as of now, fails to reflect the huge number of people we’ve spoken to through this Project. So we feel that Community leaders can help facilitate the identification process as they may know many families in Asian communities and would therefore know who, if anyone, has been tortured by the Pakistani police.”

So what does Reprieve plan to do with their evidence?

Nawaz says the information will be collated into a report which will be used to aid people like Naheem and Rehan who have found themselves at the mercy of the Pakistan prison and justice system.

“The report will be used is to aid any British national facing the death penalty as a result of confessions extracted through torture,” Nawaz says.

“This will be done by taking a test case to the Supreme Court of Pakistan and getting a verdict which will make evidence extracted through torture, inadmissible in court.

“The report could also be used to defend anyone who faces false charges as a result of a confession extracted through torture. This will be done before the case goes trial, ideally when the challan (formal charge) is filed before the judge.”

Nawaz is confident the Project will reach its ultimate goal of eradicating torture in Pakistan’s prison system.

He says: “If we get the level of victims coming forward which we expect, we really do feel we can change the police system for the better. British Pakistanis shouldn’t have to go through what my father and family went through. It is far too easy for police to fall back on torturing people until they confess to crimes which they, in all likelihood, haven’t committed.

“We hope that our Project will go some way to make it more difficult for the police to torture people and make them think twice before mercilessly beating a British Pakistani who is only in Pakistan for a wedding or to visit extended family.”

If you can help the Project in anyway e-mail Nawaz at nawaz.hanif@reprieve.org.uk Anyone interested in finding out more about the Project can go to http://www.reprieve.org.uk/pakistanpolicetortureproject