How one woman refused to be caged by her culture

Everybody looks back on their childhood with great fondness. Everybody that is except Ferzanna Riley.

Everybody looks back on their childhood with great fondness. Everybody that is except Ferzanna Riley.

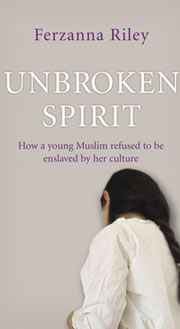

In her debut autobiographical book, ‘Unbroken Spirit’ the Pakistani-born author and journalist describes a harrowing story of abuse and fear which led her to Pakistan, trapped and helpless alongside her younger sister as her family attempted to force her into marriage. Unlike many others, Ferzanna was able to escape from her own personal hell and through her own courage and determination gave us “Unbroken Spirit’.

A small section from the book reads: “To my horror and disbelief he grabbed a big knife from the kitchen and, roaring that he was going to butcher me like an animal, he pulled my head back by my hair, exposing my neck, and held the knife across my throat. I was barely conscious, aware only that these were the final moments of my life. My sister fell to her knees, hands clasped, weeping and imploring my father not to kill me. Only then did his fury subside and he released me. Then he went out, leaving us both cleaning up the mess, sobbing from the fright of what had just happened. My father had almost murdered me by cutting my throat. I was six years old”.

Heavy stuff indeed, but as the newly appointed director of Roshni – a charity that raises awareness and offers support and advice for victims of childhood abuse in all its forms specifically within the ethnic minority communities – Ferzanna is able to help those who went through exactly what she did.

In the following interview Ferzanna reveals why she chose to write the book and how her experiences have changed her as a person.

How difficult was it to have to remember your traumatic childhood for the book?

I’ve always kept diaries since I was young and you can never forget the kind of childhood I had. However, for many years I kept the memories locked away until such time as I was ready. Revisiting them was only possible when I was in a safe place in my life with a husband and in-laws who loved and supported me.

Nevertheless even then some memories have been more painful than others, such as the beatings and the Pakistan episode. Once you allow yourself to remember, your mind releases the memories cautiously and then they rush at you like a torrent. I’d write through the night until the early hours of the morning, unable to stop. Then, completely exhausted, I’d crawl into bed and sob myself to sleep. My husband would usually wake and hold me until I fell asleep. That’s how I got through the twelve months it took to write the book.

What made you want to share your story with others?

Since I was young, I’ve always wanted to be a journalist and a writer. I have a diary entry when I was seventeen mentioning my book. I always knew that however many books I wrote, this is one book I’d always write.

I eventually wrote the book many years later, not sure whether anyone would be interested and was thrilled when having written just a few chapters, I was immediately signed up by an agent and then got signed up by a major publisher soon after. Since then there has been phenomenal media interest in both the book and the author. It’s been the scenario that every writer dreams of.

Did you make any members of your family aware of your intentions to write the book?

I discussed the book with my younger sister. She was always there as my witness through most of the things I wrote about, obviously because we grew up together. But also because she and I shared experiences that no one else would understand, either because they didn’t believe us or because they weren’t there. I wanted to make sure everything I wrote was true and accurate so from time to time I’d call her to check dates, incidents and facts.

She only read the book after it was published. I was fairly anxious about her reaction because I knew she’d tell me exactly what she thought, although it would’ve been fairly painful for her to relive some of the events in the book She called me a few days later and asked why I’d toned it down so much because some things were worse then how I’d described them. She has given the book her complete support.

Have you had any negative responses to the book?

I battened down the hatches, put on my hard hat and prepared myself for the onslaught. Surprisingly, it hasn’t happened. Most people have said it’s a balanced portrayal. I got called a ‘coconut’ on a live phone in but if you read the book, I’ve been called much worse!

Have you had any positive responses to the book?

The general response to the book has been phenomenal. Unbelievable. Male journalists have confessed that in truth, it wasn’t really the kind of book they’d read and they’d picked it up simply to give it a professional skim through prior to an interview, then found themselves hooked, using words like ‘a real page turner’ and ‘hard to put down’. One woman complained that her husband and children didn’t get fed for two days until she’d finished reading my book. I was told by another that she was gutted when she’d finished the book because she loved reading it so much and could I hurry up and write another. People say they didn’t expect to cry and laugh at the same time and loved all the funny bits. I’m repeatedly asked for the sequel.

I’ve come across some forums which discuss the book. Some have viewed it as a critique of Islam, while others see it as a critique of the Pakistani culture. Would you agree with either of these interpretations?

I’ve come across some forums which discuss the book. Some have viewed it as a critique of Islam, while others see it as a critique of the Pakistani culture. Would you agree with either of these interpretations?

This book is not prescriptive. It is descriptive. I never say in the book this is what you must think, this is how you must behave. This is my story. The things that happened to me. The choices I was faced with and the decisions I made.

Furthermore, throughout the book I repeatedly state that religion and culture are two very separate things. Indeed most of the problems begin when people confuse the two. So much is done in the name of Islam that is actually not the Muslim religion but Pakistani tradition and culture.

You and your younger sister, Farah, were very nearly forced into marriage during your stay in Pakistan. How do you look back on that event now knowing how much of an issue Forced Marriages have become in this country over the past few years?

Looking back on our experiences, I doubt that our parents would do things any differently. Arranged marriages are a very good thing and I was willing to have such a marriage. In an age where children have no respect for elders and where divorce is rife, the Asian system works. Unfortunately when parents refuse to consider the rights and feeling of the girls concerned (and it is almost always girls) then an arranged marriage becomes a forced marriage which is morally wrong and an infringement of human rights.

You are patron of the Roshni Charity. Tell us a bit about the charity and your role within it and how you think your experiences when you were a child has helped you in your role within the charity?

I am a newly appointed director of Roshni (which means ‘light’ in Urdu) Roshni is a charity that raises awareness and offers support and advice for victims of childhood abuse in all it’s forms specifically within the ethnic minority communities. Victims from ethnic communities face additional barriers not faced not non ethnic victims such as the reasons I’ve just outlined, such as shame and honour. My role within the organisation is to raise awareness of these issues using my profile as author of Unbroken Spirit and someone who has suffered first hand experience. Very few people realise that the abuse that I suffered as part of my daily life is routine in many ethnic minority families across the UK. Having felt the acute isolation that comes with abuse, I will be able to make a real contribution to Roshni’s efforts to understand and reach those most at risk.

Do you think there is enough being done to tackle child abuse within the Asian community?

No community likes to have its problems made public and Asian society is no different. There is reluctance to report offences to essentially ‘white’ organisations in addition to the cultural barriers such as shame and honour which I’ve already outlined. By writing my book and speaking about my experiences in the media and the work of my charity, Roshni, I am doing my part to raise awareness and also inspire people to believe they can overcome the problems of their past.

Working with the charity must bring you into contact with children who have been in the same situation as yourself when you were a child. Is it difficult being constantly reminded of your childhood?

On the contrary. I no longer fear my past. It no longer has the power to hurt me. My Christian faith has healed me. You can’t help your past but you can choose to decide your own future. I chose to forgive. I chose to be happy. I’ve taken back control and responsibility for my own life.

Finally, since the books release have you had any regrets writing it?

I used to shake my fist at God asking Him why if He allowed these things to happen to then why did he give me a meek, submissive, compliant nature that accepted my fate like most other Pakistani Muslim girls. Why did He give me a forceful, belligerent nature that fought back and refused to accept my fate, because it only made my situation worse. Since the book was released I’ve appeared on television and radio, done interviews for magazines and newspapers talking about my experiences. I receive letters from women telling me they read my book and wept because they identified with the things I’d written about and that I’d inspired them to believe that they too could be happy. It’s only now that I understand God’s plan for making me to be how I am. So no, I have never had any regrets about writing the book.

‘Unbroken Spirit’ is available to buy for £12.99 from all good bookstores