Charity Karma Nirvana stage three-month tour across Britain

“So many people were alerted, I told them, but no one helped because they thought I was a teenager seeking attention.”

These are the chilling words of Saima who at the age of 17 was forced by her wealthy middle class parents into marriage with an older cousin in Pakistan. Her harrowing words echo the experiences of countless other British Asian girls who had nowhere to turn during a time when the term ‘Forced Marriage’ was un-heard of.

Six months after Saima’s ordeal the Forced Marriage Act became law.

It came too late for her, but since then hundreds of other British Asians – male and female – have been saved.

The government’s Forced Marriage Unit say they take about 5,000 calls a year. On top of this hundreds of young women and men are rescued by the government from abroad every year.

Yet many in the communities where it occurs are not prepared to admit anything is wrong – and most people in the wider population don’t have any idea it is happening.

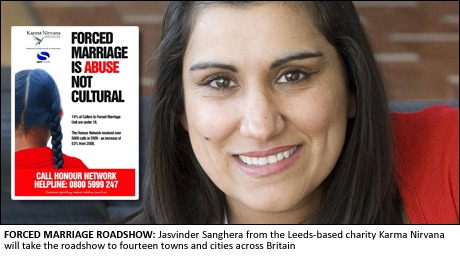

Over the next three months a special campaign of roadshows will tour fourteen cities and towns – including Birmingham in June – talking to professionals from the police, domestic violence teams, child protection bodies, health workers, schools, social workers and charities on how to deal with the issue and ways to help potential victims.

The timing of the campaign is crucial. It is no accident that this time of the year marks the start of a desperate surge in calls to specialist helplines as the long summer school break approaches.

Heading the roadshows is Jasvinder Sanghera from the Leeds-based charity Karma Nirvana.

She hopes the campaign will not only provide vital information to those in positions who can help, but also help raise awareness among the general community so they will be able to play their part in overcoming the mistaken assumption that the problem is a cultural one.

“It is not a cultural problem, it is abuse,” says Jasvinder, whose campaign has support of the government and who has been consulted by Prime Minister David Cameron.

“The sooner people start to regard forced marriage in the same way they do domestic violence the better it will be for those affected by it.”

She started the Leeds-based Karma Nirvana – the words mean ‘peace’ and ‘enlightenment’ – to help all victims, male and female, of forced marriage and honour based abuse and operates a much-in-demand helpline which takes more than 400 calls a month.

“It’s not a popular issue for some people, in fact for many it’s a very unpopular issue,” said Jasvinder.

“We take a lot of flak from communities, and there are risks for the people who try to help us. However one of the difficulties we find is that some professionals are afraid of being called racists. But it’s not about race, it’s about abuse.”

The roadshows will also explain the workings of the Forced Marriage Act, which offers protection to those at risk – often preventing them from being taken out of the country. Last year, about 400 people were repatriated to the UK after being taken away against their will.

The youngest caller to the group’s helpline has been aged eight, and the largest age group is between 12 and 21.

“Every year there are 12 murders so-called honour killings, in this country,” says Jasvinder, whose own sister committed suicide to escape a forced marriage.

Critical to the success of the roadshows will be the testimony of a courageous group of survivors who will talk of their experiences to the thousands of delegates present.

Jasvinder, 45, who survived similar experiences at the age of 16, said: “Their stories can be both harrowing and inspiring, but always very moving”.

For Saima her experience is both harrowing – of how she survived hardships, a breakdown, of a hitman’s ‘honour’ knife attack which killed her unborn baby, and of being cut off from the family which claims she shamed them – yet also inspiring in how she found the strength to fight back and rebuild her life.

This is her story:

“The worst thing was the fact that so many people were alerted, I told them, but no one helped because they thought I was a teenager seeking attention. Hopefully, now the law has changed, places like schools, colleges and people like social workers, police and doctors will take this more seriously than they did even just a couple of years ago.

We always think that forced marriages happen to poor people back home with no education. That’s the mentality. I have to point out that both my parents were educated, they went to university in this country and had a love marriage

I was privately educated and a very comfortable life – horse riding, hunting, golf, swimming, all the luxury I ever wanted – but it still happened to me. It can happen to anyone. I had told my parents that an arranged marriage just wasn’t going to happen, but they told me I did not know my own mind. My mother told me I lived in a teenager’s fantasy world.

The second time I went to Pakistan I thought it was another holiday, my parents said they wanted me to absorb the culture, and that’s what I thought was happening.

When my father took me to the airport his friend was waiting to accompany me on the flight. They took the chip out of my phone and this man followed me everywhere, even on the plane when I went to the toilet.

In Pakistan, the first thing my aunt did was take my passport and return ticket off me.

Then when I opened my suitcase, which my parents had packed for me, it was full of wedding stuff. I thought I was going on holiday but it was my worst nightmare and there was no escape.

My parents flew across for the ceremony but just stayed two nights. I sat and cried through the whole thing, weeping and weeping.

Later my mum dragged me into the car and took me to my husband’s house and left me in the bedroom. There was no water or electricity in the house, my husband was unemployed and had no money and I sat on the broken bed and thought ‘How am I going to survive?’

I got a job teaching English at a local school, 12 hours a day, six days a week. It was great just to get out of the house because my husband was very abusive – hitting was normal for him, throwing ornaments at me and threatening me.

It would have gone on for years, but when I got pregnant I decided I wanted my child to have everything in life I did, so I was allowed to return to Britain after promising I would help my husband get into the country.

When I got back I arranged to meet a former sixth form teacher and she took me to the police.

After I had left home a man approached me in the street with a knife, telling me to go home. When I refused he attacked me, and I woke up in hospital to be told my child had died.

I have siblings and even today I still wish I could go and see them and my mum and my dad but I know it’s not going to happen, they’re not going to change and they don’t want to know me. I think they thought I had brought shame on them and brought dishonour on the family.

“I remember talking to my mum and telling her everything he had done to me. Everything, and every way he abused me. I was crying. I remember her words she told me: ‘He’s your husband. Even if he kills you we don’t care because you’re no longer our property.”

If you’ve been affected by the issues raised in this article and would like to talk to someone call Karma Nirvana’s Honour Network Helpline on 0800 5999 247. Alternatively you can visit their website at www.karmanirvana.org.uk